Safe Routes to School first started in United States in the 1990’s as projects in a few cities and one state. In 2005, Congress approved funding for implementation of Safe Routes to School programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. From 2005 to 2012, Safe Routes to School initiatives were funded through a standalone federal Safe Routes to school program. This program provided more than $1 billion in funding in all states to support infrastructure improvements and programming to make it safer for children to walk and bicycle to and from school.

In June 2012, Congress passed a new transportation bill, MAP-21. This legislation made significant changes to funding for bicycling, walking and Safe Routes to School. The federal Safe Routes to School program was combined with other bicycling and walking programs into a program called Transportation Alternatives. Safe Routes to School projects are called out as being eligible for Transportation Alternatives, but no minimum funding level is required. This funding stream was locked in for five additional years--with some changes--when Congress passed a new transportation law, the FAST Act, in December 2015.

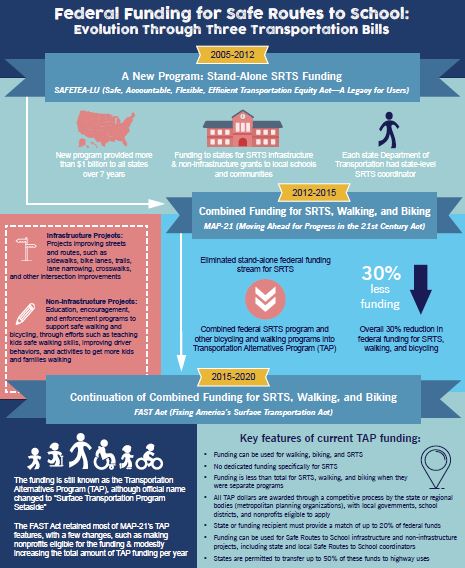

This infographic provides an overview of the funding history of Safe Routes to School through three transportation bills. Keep reading for a deeper dive into the legislative history and legislative text of the federal Safe Routes to School program and of the Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP)--newly renamed the STP Setaside.

Overview of the Federal Safe Routes to School Program

In a sweeping effort to get more children walking and bicycling to schools across America, Congress approved $612 million over five years (FY05-09) for a new federal Safe Routes to School program as part of the federal transportation bill, SAFETEA-LU, which was adopted on July 29, 2005 and signed by the president August 10, 2005. Congress extended the program at $183 million per year from FY2010-FY2012, resulting in more than $1 billion dedicated to Safe Routes to School.

Each State Department of Transportation (DOT) received annual federal funding from FY2005-2009 to implement the program. A state’s share of funding is based on the number of children enrolled in primary and middle schools (K-8), with a minimum allotment of $1,000,000 per year. Each state was required to have a full-time Safe Routes to School coordinator to administer the program.

The purposes of the program and funding were:

- To enable and encourage children, including those with disabilities, to walk and bicycle to school;

- To make bicycling and walking to school a safer and more appealing transportation alternative, thereby encouraging a healthy and active lifestyle from an early age; and

- To facilitate the planning, development, and implementation of projects and activities that will improve safety and reduce traffic, fuel consumption, air pollution in the vicinity of schools.

State DOTs may make grants to state, local, and regional agencies, including nonprofit organizations, to implement Safe Routes to School programs. The federal share for the grant was 100%.

Eligible activities for funding under Safe Routes to School included both infrastructure projects and non-infrastructure related activities. States were to spend 70-90% of their funding on infrastructure projects that improve safety for children walking and bicycling to school. All improvements had to be made within a two-mile radius of school. Eligible activities include:

- Infrastructure: Funds may be used for the planning, design and construction of projects that will substantially improve the ability of students to walk and bicycle to school, including sidewalks improvement, traffic calming, speed reduction improvements, street crossings, on-street bicycle facilities, off-street bicycle and pedestrian facilities, secure bicycle parking, and traffic diversion improvements in the vicinity of schools.

- Non-infrastructure: Funds may be used to encourage walking and bicycling to school, including public awareness campaigns, outreach to press and community leaders, traffic education and enforcement in the vicinity of schools, student sessions on bicycle and pedestrian safety, health, and environment, as well as funding for trainings, volunteers, and managers of Safe Routes to School programs. From 10 to 30% of the amount apportioned to each state will be used on non-infrastructure related activities.

The legislation also established a Safe Routes to School Clearinghouse—called the National Center for Safe Routes to School—to provide technical assistance to local SRTS programs and state SRTS coordinators. The Secretary of Transportation was also required to establish a national Safe Routes to School Task Force to assess the implementation of SRTS and make recommendations to advance the program.

Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP)

In June 2012, Congress passed a new transportation bill, MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century), that made significant changes to funding for bicycling, walking and Safe Routes to School. Under the new law, Safe Routes to School is combined with the former Transportation Enhancements program and Recreational Trails program into a new program called Transportation Alternatives. Congress also added some new eligible uses, including environmental mitigation and boulevard construction.

The funding level for all these uses combined is approximately $800 million per year, which is a cut of more than 30 percent from the $1.2 billion allocated in FY2011 for the three bicycling and walking programs. Plus states can opt out of using half of the Transportation Alternatives money. As a comparison, in FY2011, Safe Routes to School alone was funded at $202 million. Clearly there is a lot less money available overall, and Safe Routes to School projects must compete against other bicycling and walking projects, as well as the new eligibilities of environmental mitigation and boulevard construction. The amount of funding that will go to Safe Routes to School under this new construct will depend on the decision-making of state departments of transportation and the work of advocates and public officials at the local level.

All Safe Routes to School infrastructure and non-infrastructure projects that were eligible under the federal Safe Routes to School program continue to be eligible to compete for funding under Transportation Alternatives. However, these projects are no longer funded at 100% federal funding; now local communities must come up with 20% of the project's cost as a match.

The funding also has a different way in which funds will flow. Out of the $800 million available for Transportation Alternatives:

- States first allocate $85 million to Recreational Trails, unless they opt out of doing so.

- Of the remaining funds, half of the Transportation Alternatives funding are allocated by population to metropolitan planning organizations and more rural areas. Metropolitan planning organizations with a population of 200,000 or greater will receive their funds through suballocation and will hold grant competitions for their share of the funding.

- The other half of the funding will be awarded by state departments of transportation through grant competitions, unless they opt out of this portion completely and transfer it to other highway uses, which is permissible.

Safe Routes to School coordinators are no longer required, but are allowed to be retained and funded using Transportation Alternatives dollars. In addition, any of the original Safe Routes to School dollars that remain can continue to be awarded by state departments of transportation under the old rules. As of December 2014, there is approximately $150 million remaining to be spent. The National Center for Safe Routes to School is also no longer required, but can be continued by the US Department of Transportation using discretionary dollars.

Bicycling and walking infrastructure (including Safe Routes to School projects) continues to be eligible under all highway programs, including the Surface Transportation Program (STP), Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ), and the Highway Safety and Infrastructure Program (HSIP). New requirements under HSIP require better data‐gathering on bicycling and walking crashes and safety.

Changes to the Transportation Alternatives Program in the FAST Act

In December 2015, Congress passed a five-year transportation bill, the FAST Act (Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act). It preserves funding for Safe Routes to School, bicycling and walking for five additional years without many changes to the Transportation Alternatives Program.

The Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP) is renamed to “STP Setaside” and was moved to be a sub-program of the Surface Transportation Program, a large and fairly flexible pot of federal transportation dollars available to state and regional governments. While the program was renamed at the federal level, states and regions can continue to use the TAP name.

While the name may have changed at the federal level, most of the program did not change. It will still operate in large part as it did when it was created under the last transportation bill, MAP-21. A few highlights on how the program operates just as it did under MAP-21:

- Safe Routes to School (both non-infrastructure and infrastructure), walking and bicycling projects are all still eligible to compete for funding. States can run one big TAP competition or can choose to separate out Safe Routes to School as a separate competition.

- Projects do require a state or local match of up to 20 percent of the project cost.

- Decision-making is still split up between state and regional governments. State departments of transportation will still control 50 percent of TAP funds to either award to projects or transfer to other uses, and the other 50 percent is targeted for projects in small towns, mid-sized communities and larger urban areas. For large urban areas with more than 200,000 people, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) run the competitions and pick the projects.

- All TAP dollars have to be allocated through a competitive process that the states themselves are not eligible for, giving local governments and schools systems the opportunity to put forward the projects that are most important to their communities.

There are some changes, positive and negative, that Congress made to TAP:

- Funding will grow from the current level of $819 million per year to $835 million in 2016 and 2017 and to $850 million in 2018 through 2020.

- State and local nonprofit organizations that work on transportation safety will now be eligible to compete directly for TAP dollars (joining the already-eligible local government agencies and schools/school districts).

- In large urban areas, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) can choose to use up to have their TAP funds for non-TAP projects—though those projects would still have to go through a competitive process before being selected.

- The US Department of Transportation is required to issue new guidance that makes it easier for TAP and other transportation projects to move through the regulatory process more quickly. While it will take up to a year for this guidance to be developed, we hope it will make it easier to move forward on Safe Routes to School projects.

- There are new reporting requirements that we hope will make it easier to know how states and MPOs are allocating their TAP funds.

Outside of TAP (or the “STP Setaside”), Safe Routes to School, bicycling and walking infrastructure projects are still eligible for funding under all highway programs, including the Surface Transportation Program (STP), Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ), and the Highway Safety and Infrastructure Program (HSIP). There is also a new funding stream to support high-risk states in implementing bicycle and pedestrian education and enforcement programs that will be implemented by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.